RELEASE DATE: August 18, 2017

DIRECTOR: Doug Nichol

MPAA RATING: NR

RUNTIME: 104 minutes

The typewriter holds a certain romanticism. It’s more permanent, more mechanical, more direct than any word processor could ever dream of being. That it is an obsolete technology makes the appreciation of it even stronger, because now it’s relegated to cultural nostalgia and the enthusiasm of collectors. California Typewriter follows the many ways in which a continued love for the machine exists in a society that has otherwise discarded them.

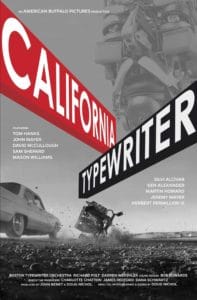

You can still find practical users; Tom Hanks, John Mayer, Sam Shepard and David McCullough are showcased here as those who have or had used typewriters in their daily workflow into the 21st century. There are collectors who spend colossal amounts of time and money in maintaining what amounts to small, personal museums, and they’re always on the lookout for more. And there’s an artist, who takes apart old, dilapidated typewriters and uses the parts to create metallic sculptures, often of humans, and has attained moderate success in the art world. He often gets the machines from a shop called California Typewriter, located in Berkeley, Calif., from whence this film receives its name.

It’s a tiny, family-run business. They recognize the precarious nature of their endeavor but hope that a new interest in typewriters will spark a rebirth. Director Doug Nichol makes a sturdy case for the possibility of this, showing that there are both technical and artistic reasons to why we should not forget about them. California Typewriter is a movie sympathetic with the idea, devoting much of its runtime to pondering how we can reconcile the onward march of progress and the desire to hold together our collective memory of the past.

Perhaps Nichol is too excited by his subject. The documentary winds up taking a scattershot approach, with an uneven balance of its subjects. Interviews with its most famous subjects are cut up and scattered throughout, but long segments devoted to the collectors and to Jeremy Mayer, the artist who repurposes typewriters, take up lengthier chunks. California Typewriter spends more time on them than it does on its titular business.

It becomes one of the few films where a runtime of under two hours feels self-indulgent. A vignette that bookends the film, describing the 1967 Royal Road Test, in which Edward Ruscha threw a typewriter out of a moving car and photographed the aftermath, has nothing to do with the rest of the movie. In effect, Nichol has made a loose series of short subjects about different aspects of typewriter culture and has decided that it should be a feature. The disjointed editing makes it hard for him to form a central thesis. All we’re consistently told is that people still like typewriters. And…? Isn’t there a greater point somewhere?

What ends up happening is that California Typewriter lives and dies on the visible passion of its interviewees, and the implied passion of its director. That works. From Hanks, who insists that typewritten memos are the only real way to send correspondence, to collector Martin Howard, who has spent decades pining after one early typewriter and is ecstatic when he encounters one at a museum and tries out the keys, our interest is held because we’re watching people who care.

A diatribe that springs up in the last 15 minutes from a number of commentators about how the printed text is a form of rebellion in a digital world builds a fun, quirky rhythm. When Nichol sits back and lets things happen, the film is at its best. But he casts his net so wide, so rapidly, so early that such moments of zen are rather inconsistent.