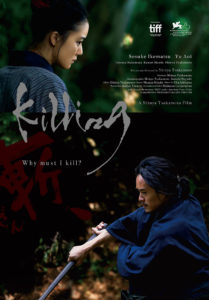

Director: Shin’ya Tsukamoto

MPAA Rating: NR

Run Time: 80 Minutes

With his latest, maverick actor/director Shinya Tsukamoto continues his later career’s exploration of more traditional genre forms examined under his iconoclast perspective with the condensed and eclectic samurai drama Killing. Taking up where his last “traditional” film, the 2014 remake of Ichikawa’s 1959 Fire on the Plain left off, Killing plays like a psychological destabilization of the samurai mythos caught between rigid convention and the director’s patented subversion.

The look and content hearkens back the lauded jidaigekis of Japan’s oldest and proudest film tradition faithfully, but Tsukamoto paints a more personal and cerebral picture of the samurai figure (and his ever-present weapon) unlike his predecessors. The effect is a film almost removed from Japan’s film history, an identity all its own for better or worse.

Set during the Edo Period, it centers on a deserting ronin, Tsuzuki (Sosuke Ikematsu), who has taken on life of peace and idleness with a small farming community during the extensive peace in the mid19th century. His sense of adopted community and the indolence of peasant activities – sparring with farmhand/samurai hopeful Ichisuke (Ryusei Maeda), assisting the rice harvest and pining for the love of Ichisuke’s sister, Yu (Yu Aoi) – relieves him of his existence fighting under the loyalty of a lord.

Only when news of an impending civil war by way of a skilled fellow ronin, Sawamura (Tsukamoto) does his idyllic worldview come crashing down, the superior swordsman recruiting him to travel to Edo and causing Tsuzuki to become caught between two worlds of simple desire and class expectation. A chain of events is triggered that places the act of killing for loyalty, vengeance, compulsion or otherwise under intense scrutiny and leaves nearly all involved (unsurprisingly) bloody.

Tsukamoto may be working in new genre constraints (his only film close to a pre-modern period piece being the 1999 Gemini set in the Meiji Era), but he proves more adaptable to the look and feel of the samurai film than first assumed. His frenetic, dizzying, handheld cinematography offers a bold spin on the normally clean-cut chambara action the genre promises.

Fight scenes become these hyperactive flurries of steel, bodies and arterial sprays of blood, difficult to read but quite easy to feel out the tension. Accompanied by the concussive soundtrack of longtime collaborator Chu Ishikawa, who, in his last score before his death, brings an industrial music sensibility to traditional percussion, the film strikes an uneasy balance between these kinetic scenes of action and more meditative and muted compositions that are more reminiscent of the samurai genre as a whole.

Finding this balance upholds a lot of Killing’s momentum in the first half, but when it breaks through that transitional space of the director feeling out the genre, it never looks back and seamlessly blends the two aesthetics. More radical than his look is Tsukamoto’s scope and intention for the film in how, unlike your average samurai film that teases grand-scale battles and skill-testing showdowns, he scales it all back to one man’s objection to his very essence of his caste: the use of his blade to take life.

Tsukamoto has said the film was inspired by a solitary image of a young ronin looking at his sword in ardor and confusion, and that thematic distillation plays out eloquently on the screen. Even with Tsuzuki being called to raise his sword in the classical names of honor and revenge, he fascinatingly remains conflicted, this existential crisis serving as the linchpin in Killing’s subversion.

Tsukamoto is even so unrestricted to incorporate a psychosexual dimension of Tsuzuki’s strained relationship with Yu, conflating anxiety over killing with sexual frustration in a darkly comic subplot. Outside of a muted issue with bandits taking residence at the periphery of the farming village, which fuels the film’s low body, the conflict in Killing remains deeply internal and illusory, ending in a non-climax of the grievously injured participants chasing each other through the labyrinthine forest in a surprisingly engrossing struggle between the samurai and his status.

Those expecting the director’s cyberpunk roots to pollute the sanctity of the samurai film will surely be disappointed, but it cannot be emphasized enough that Tsukamoto’s relatively low-budgeted rendition of the filmic tradition is every bit as radical as you would expect from the mastermind of the Tetsuo series. Through a shaky hybridization of styles between his work and traditional genre aesthetics by scaling the scope back and building a rich interiority for his characters, Killing becomes a samurai film unlike any other.