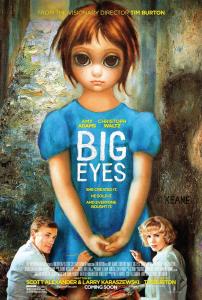

Release Date: December 25, 2014

Director: Tim Burton

MPAA Rating: PG-13

Big Eyes may be the least Burton-esque of all of Tim Burton’s films. There are a few touches that remind you that he is behind the proverbial curtain, but by and large, the film feels directed more by the performances of Amy Adams and Christoph Waltz than by Burton. This is not a criticism. Adams, Waltz and Burton have created a minor gem with their telling of this true story of one woman’s initial abdication of self to someone else’s control and ultimate rebirth as her own creation.

The film tells the story of Margaret (Adams) who, when it was fairly unfashionable in the late 1950s, took her daughter and left her husband making herself a single mother. She is a painter but it does not pay the bills; it is instead her passion. We find her in San Francisco doing caricatures at a street fair. and it is there she meets another painter working next to her – Walter (Waltz). It comes out that Walter is in commercial real estate and that painting is a hobby for him but one he desperately wishes he could do full time. They have a quick courtship and marry.

Ever the entrepreneur and master salesman, Walter displays his scenic paintings alongside Margaret’s pictures of big-eyed children in a fashionable jazz club. When a woman admires one of Margaret’s paintings, Walter takes credit for creating it, probably out of ego and jealousy. Margaret goes along with the ruse. Margaret needs Walter because her first husband threatens to have her declared an unfit mother and take their daughter from her. When the big-eyed children become hugely popular, Margaret finds she has no choice but to keep her mouth shut. After all, as Walter reminds her, she is just as guilty of committing fraud as he is. And he rationalizes his behavior, convincing Margaret that people do not buy women’s paintings and that they are partners in the business just as they are partners in life.

But where Walter sees dollar signs with each painting, Margaret sees a piece of her soul. Through happenstance, Margaret discovers Walter has been lying about more than just her paintings. When she confronts him, he reveals the lengths to which he would go to keep the lie going and to keep it secret. Margaret reaches a breaking point, flees to Hawaii, and lets the proverbial cat out of the bag on local radio. This leads to a lawsuit, and, in a courtroom scene one could see coming from miles away, the two are put to the test when the presiding judge asks them each to create a big-eyed child painting. The rest is, of course, history.

The film is mostly light and airy, but the dramatic stakes could not have been higher at the time the events were occurring. I do not mean to create a pun here, but the film at times feels a bit too “paint by numbers.” It is not a demanding screenplay and one that I imagine Burton, Adams and Waltz could have worked out in their sleep. Adams elicits sympathy from an audience but not in a melodramatic way; she is utterly believable as a simultaneously fragile yet strong woman who finally finds her own voice. Waltz has the trickier job of playing the piece’s villain without being unwatchable. He walks a fine line throughout the film and does a terrific job of convincing us of how Walter could be so charming while living life as a self-centered man-child who has conflated wanting to be someone special with actually being special oneself.