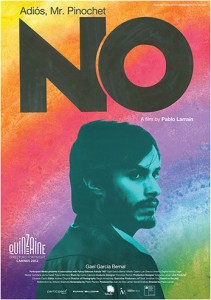

Director: Pablo Larraín

MPAA Rating: R

Remember the ad campaign ‘Just Say No To Drugs’? I was young, possibly 5 or 6 years old, when the campaign swept the education system with its jingle…’Just say no, Just say no to drugs!’ With Magic Johnson twirling a basketball on his fingertips for what seems to be an eternity, every 80’s latch-key child was hypnotized into the campaign with star power, celebrity, and a catchy jingle. Eventually culture found that ‘Just Say No’, was not just that simple. Now imagine you are a Chilean of the same age, and instead of the drug jingle and basketball players, you remember a message about happiness filled with all the same spectacle, one which “looks like a Coca ~ Cola ad”, promotes fun, happiness, and freedom using a ‘We are the World’ styled jingle all neatly tied up under the same word, No. This is the stage of Pablo Larrain’s No.

The title itself refers to the advertising campaigns that were used to vote for or against Pinochet’s extended term as a leader, a constitutionally required referendum to gage the desire of the people to be under his militant dictatorship. René (Gael García Bernal), is an art director for the No Campaign and father of a young boy whose mother is an activist rebel, constantly in front of the police in protest to the harsh realities of a 1988 Chile, and whose character serves to show the nature of dissent in the country. There are two separate campaigns for the vote, Si, and No, which are allotted 15 minutes of marketing on television every night for a month before the vote. René’s character is built into this otherwise true story, a probable composite character amidst a swirl of clips from the actual campaign. With a vision of what works in marketing, he successfully persuades the No campaign to take a highly commercialized direction. Using inventive strategy based on the fact that Pinochet’s campaign has, with the long arms of dictatorship, appropriated ‘democracy’, team No decides to fight back by marketing ‘happiness’. Rainbows, picnics, and images that look as though they were cut straight from a Double-mint gum commercial are the high energy messages which powerfully overturn the fear that the election is a fraud, and that anyone who votes against Pinochet is a target for death or disappearance.

In advertising, nothing is as simple as it looks, and you can draw the same conclusion from such a direct and simple title. The camera work is often on the soft side of focused and the image quality is limited at best, but the film itself is shot on a 1983 U-Matic video camera, in an attempt to remain true to the aesthetic of a 1988 Chile. Indeed, we are reminded early on in the film that this is a time when the microwave has freshly arrived on the scene. The camera work is not there to wow us with a HD visual display of the location and the spectacle of tear gas and street riots, peaceful protests and video shoots. In fact, the choice against HD was very purposeful, an act of saying ‘no’ in its own right, and beauty is not really the concern of the film. Through this visual style Larrain asks the viewer to take on the perspective of the camera, to enter the world and get dirty as a result, which serves to remind us that this subject is not easy, and does not have a pretty face.

Interestingly enough, what Larrain asks us to witness in the final installment of his trilogy is something he himself missed as a child. When interviewed, he openly states that in making the trilogy, he tried to expose the fear and violence that he did not personally witness as a child in Chile. An outsider as the protected child of a senator of the political ‘right’, he admits he was unaware of the political events in his country until he was 15 years old. As the film closes, we recognize this perspective in René’s character, who, amidst a country in celebration and exaltation, remains emotionally disconnected from his own sense of victory. In the final scenes, as he returns to his work of selling soap operas and lifestyles, we are privy to the natural conclusion of the emptiness in marketing. A worldly message, it’s hard not to wonder how Shepard Fairey might react to such a film. After all, manipulating ideas for a mass culture in order to influence their vision of the world they live in, do you get to experience the change you promised? In any case, this film reveals, for better or for worse, that political testimony, art, and rebellion are not the only keys to change. In fact, they may not function at all in the face of good old happiness.