MPAA Rating: Not Rated

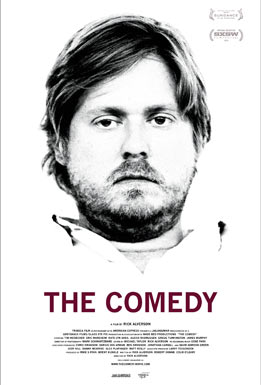

Director: Rick Alverson

FilmPulse Score: 7/10

The Comedy is not funny. It has its moments, but overall there are little laughs in this film about a guy from Williamsburg aimlessly passing time. The Comedy is Rick Alverson’s third film, and perhaps the first to garner much attention in the mainstream. This is likely due, in part, to the contributions of Tim Heidecker, who stars as the leading character in the film, and Eric Wareheim of The Tim and Eric Awesome Show Great Job and Tim and Eric’s Billion Dollar Movie. The film is a departure from the sorts of off-the-wall comedic roles that audiences are accustomed to seeing the pair playing, but in The Comedy, both actors demonstrate their ability to act in serious roles as well, while still displaying their irreverent sides in full force.

The Comedy tells the story of an aging, aimless Brooklynite who wanders through his life offending nearly everyone and doing nearly nothing. Heidecker’s character is as unlikable as they come, while still managing, somehow, to be almost pitiful in his directionless and nearly solitary existence. His character is so extreme, so over the top that he is almost a caricature; still, he is just believable enough that you may find yourself questioning whose side you should take.

Very little happens in The Comedy – so little that it would be difficult to give any sort of traditional plot summation. The film is an exemplary example of a powerful character study. But one gets the sense that Heidecker is not just playing a character, but an amalgamation of many personality types present in contemporary society, particularly among his age group. The carelessness that he displays, the seeming pointlessness to everything he does, can be seen as not only unique to his character or, even, many character types – his traits are part of something so much larger. Indeed, perhaps, his character is representative of not only the types of individuals that make up modern society, but society as a whole. Heidecker’s character is often described as a hipster type – a term which, personally, I am not too fond of. The term has become so broad, so all encompassing that it now seems almost arbitrary. To pigeonhole him as a hipster is to do an injustice to the character that Alverson has so carefully sculpted into someone so complex that I would guess nearly every viewer can relate to in some way.

Heidecker’s character is adrift in a world that may be too big for him. His desperation is apparent as he pathetically reaches for attention and affirmation through crude, offensive humor. He has several friends who, it is safe to assume, lead similar lives to his own. One of the film’s more memorable scenes shows several of the guys gathered around talking jocularly about their feelings for one another, yet still it is easy to question their sincerity; it is almost as if they are trying to prove something to themselves – that they do matter to one another in spite of the fact that they are all so obviously, inescapably alone. When he does manage to (awkwardly) get “close” with a female coworker, the evening they spend together culminates in her having a seizure, while Heidecker stares stoically at nothing. He gives her a ride back to Manhattan in his boat, and they end the evening with a casual but no less forced “see you at work.” Any connection they may have had had been severed – he made no attempt to help her, no attempt to connect with another human being.

In the most poignant scene of the film, the guys from earlier are gathered in a living room while Wareheim’s character shows old slides on a projector. Solemnly he points out siblings and parents and places he once had cared about (assuming, that is, that they ever really existed in the context of his life). Everyone in the room stares fixedly and mostly silently as he flips through the slides. Even the startlingly placed photos of naked women garner no response. The true extent of their apathy is, if it hadn’t been already, devastatingly apparent. The scene with Wareheim provides perhaps the most clarity and the saddest insight into the film: that is that once we are grown and in the larger world, away from the family and home that once created the extent of our existence, we are, in most respects, alone, just trying to fit in.