MPAA Rating: NR

Director: Alex R. Johnson

Run Time:

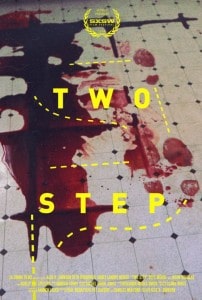

Small town crime dramas of the Southern persuasion, with their glut of Southern-drawl colloquialisms liberally interspersed throughout a landscape of violent, homespun justice and double/triple crossings, are a familiar sight and Alex R. Johnson’s Two Step is as about as familiar as they come. A film populated with (just about) every element generally associated with crime narratives – idiom-heavy dialogue, vintage autos, inexplicable criminal networks, et al. – Two Step has it all, except for the one element it desperately needs – conviction.

Thoroughly pedestrian in every way, Two Step suffers from a debilitating lack of energy and vigor, shuffling about from one development to the next, seemingly never comfortable with exerting itself. The listlessness extends itself to all facets; the visuals and production values are far from flashy, while the plot progressions are the furthest thing from complex, as the film appears completely content with simply blending into the background of any, and all, living room across the country.

Johnson’s screenplay is the cinematic equivalent of a to-do list (not necessarily an intriguing to-do list either) entirely uninvolved with complexity, theme or any sense of tension or pace. It never attempts to elevate itself from nothing more than a rigid sequence of events. Straightforward narratives, such as these, can be engrossing in their simplicity although Johnson’s script resides squarely in the land of mediocrity, indistinguishable to the point of forgettable.

While the film appears satisfied resting on its laurels, one person – James Landry Hébert – within the production does their best to inject some emotion into the proceedings playing a small-scale con-man, hustling the elderly via telephone, erratic and volatile with a tendency towards poor decision-making along with a persistency beneficial to no one except himself. At first, Hébert fails to set himself apart, auto-pilot acting coupled with unconvincing line reading, until the story requires his character to escalate his transgressions; once, the violence intensifies and Hébert’s character graduates to a multiple-felon criminal, Hébert relishes the opportunity, quickly establishing himself as the lone bright spot. He is the only one aspiring for something more; unfortunately, the film does not have the decency of reciprocating.

The cinematography, on the other hand, gives off the feeling that the camera is trying to escape. Always in a state of panning at the outset of every shot, even the camera gives off the impression that it, too, is unenthused by the display; perhaps, in search of something more captivating residing just outside the frame. Regrettably for the audience, this endless search bears little reward.